On april 30, 1994 Roland Ratzenberger was killed during qualifying fort he San Marino Grand Prix. One day before Ayrton Senna would suffer his fatal accident. Senna was world famous, a great champion whose death would create a shockwave around the world that would make Ratzenberger disappear into the shadow for ever. Roland Ratzenberger was contesting his rookie season, and was merely a footnote in the three race weekends he contested in his Simtek-Ford. He qualified just once, finished once and then came Imola and the fatal crash. As quickly as he arrived, Ratzenberger had disappeared forever. Who was this Austrian?

I’m standing on the rooftop terrace of Hotel Stein in Salzburg. “Margit and I got married here. Look at the wonderful view!” says Rudolf Ratzenberger. He’s right, the view overlooking Salzburgs Altstadt and the old fortress is beautiful. We’re here to take pictures. Pictures in which the connection between Roland Ratzenberger and the town of Salzburg is made clear. A short while earlier, in the basement of his apartment, Rudolf opened a dusty, cardboard box, captioned “Ratzenberger”. It was given to him by the Italian police at the end of 1994.

In it were Rolands belongings. His gloves, and also the helmet he wore during that horrible crash in Imola. It has a big indent on its left side, some sponsor logo’s are damaged, and its inside has come loose. It’s clear this helmet had to endure one almighty impact. “You’re the first journalist to ever see this helmet”, says Rudolf. It is special to see it. Bizarre, but special too. Rudolf insists we photograph this very helmet, and fortunately we can. The right side of it sustained almost no damage, and looks like nothing ever happened. When he reviews the pictures on my camera, Rudolf simply says: “Schön”. Beautiful.

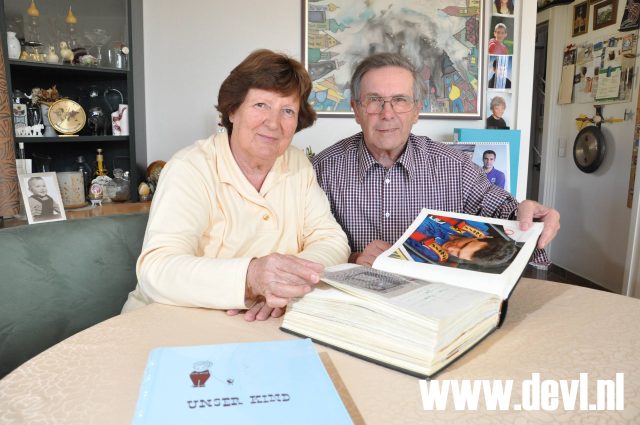

He’s proud of these photo’s, and although he doesn’t say it, I feel he’s also proud of this helmet. The only helmet he has from Rolands Formula 1-career. The helmet that embodies the great dream of his son. I’m proud he allowed me to hold that very helmet, although it tells a dreadful story. That moment was the start of a special visit to Roland Ratzenbergers hometown Salzburg. There I not only speak with his parents Rudolf and Margit, but also to his good friends Harald Manzl and Gerhard Kuntschik. “Only a few years ago I realized I miss Roland a lot more than I ever cared to admit”, Manzl says. Kuntschik too, thinks of his friend every day. “He called me after every race. “Servus, der Roland ist es”, he would say. I’d hear by the tone of his voice whether he’d had a good race or not”. His parents need even less words: “Roland lives with us”, they simply say.

One thing is certain: in 1994 Roland Ratzenberger was a very happy man. He had finally made it to Formula One, realizing the dream he decided to chase when he was a small boy. Only few people know he only narrowly missed out on making his debut in F1 as early as 1991. Eddie Jordan’s new team was very interested in the Austrian, but unfortunately for Roland the Japanese sponsor that should have helped him secure the ride, ran into problems. The deal didn’t materialize, and Betrand Gachot got the seat in the Jordan. He scored points driving that car. What if? Doesn’t matter. Ratzenberger got his chance in 1994, with Simtek, the new team of British engineer Nick Wirth. Barbara Behlau, the half-Dutch sports manager from Monaco, who got on famously well with Ratzenberger, paid half a million dollars to get Roland in the car. The Simtek wasn’t very good, and Roland only had a contract for five races. Although he knew the shortcomings of his car, he also saw perspective. “But during that fateful qualifying session in Imola Roland definitely wasn’t happy”, says his mother Margit, “he knew his car wasn’t competitive and wanted better. But he was in F1, and therefore he’d reached what he had always dreamed of.” “Roland wasn’t a euphoric person”, says Harald Manzl, “he was always in control of his emotions. He didn’t cheer, scream or dance when he signed the contract with Simtek, but I’m sure that deep down inside it was his biggest satisfaction ever.”

We will never know, but you can’t help but wonder what would have become of Ratzenberger if he hadn’t left this life in the Villeneuve-kink at Imola. That he would have started his second Grand Prix the next day was already certain. His best lap of 1.27.584 was sufficient for 26th and last place on the grid. Gerhard Kuntschik thought a lot about what would have become of Roland. He thinks he wouldn’t have become a great champion, but is certain Ratzenberger would have had a succesful career in F1. “I think he would have grown into an appreciated test-driver. You shouldn’t forget that Roland, in part because of his education, was technically very astute. I think he would have had a great career, comparable to that of Alexander Wurz. After F1 he maybe would have become an advisor, or maybe he would have gone back to sportscars. The fact that Toyota in the early 90’s paid him a 100.000 German Marks to contest Le Mans for them, speaks volumes about how they valued Roland.” Ratzenberger would have been the number one driver for SARD Toyota at Le Mans in 1994. His place was taken by Eddie Irvine, but Rolands name featured prominently on the car that would eventually finish second in the race. What cannot be contested is that, after living in Monaco, Britain and Japan, Ratzenberger would have come back to Salzburg. He bought a beautiful apartment there, overlooking the mountains. He received the keys on april 22, 1994. He never lived there. After thinking long and hard Rudolf and Margit decided to sell their old house and move in tot heir sons apartment. They live there tot his day, and as time moves on they become increasingly proud of their racing son.

Margit confirms that, but also says it isn’t in her and her husbands nature to show that pride. “We weren’t euphorical parents”, she says, “that’s just not who we are, we’re down to earth.” Rudolf Ratzenberger hesitatingly admits that he finds that difficult. “I’m not good at praising people”, he says, “and sometimes I’m scared that I haven’t praised Roland enough during his lifetime. Shortly before his death I gathered a lot of press clippings about his career, from all around the world. That made him laugh, realizing his career meant more to me than I ever let on. Like Rindt got the world title posthumously, I only learned to really value the enormous achievement of my son to simply reach Formula One after he died.” For hours Rudolf Ratzenberger talked to me about his son, but only now I hear real emtion in his voice. He can rest assured. The love for his son was obvious to hear in every word he said.

My extensive portrait of Roland Ratzenberger was published in Formule 1 in 2011.